Healthcare

An equitable health care system provides universal access to high quality, affordable, and culturally appropriate clinical care that is responsive to the social conditions that influence an individual and their community’s health. It also provides care that does not vary in quality dependent on race, gender, socioeconomic status, or other aspects of an individual’s identity. Access to health care empowers individuals and communities to actively engage in preventive and health-promoting activities, and also provides a safety net in the unfortunate event of major health crises.

High cost, inadequate insurance coverage, lack of services available, stigma in medical structures, and lack of culturally responsive and structurally competent care prevent equitable access. Stigma, racism, and cultural conflict in health care settings, for example, can contribute to health disparities.[1] Health care structures should broaden their approach to consider and address the ways racism and other systems of oppression shape patients’ experience/treatment in health care settings along the lines of race, culture, and identity. Having health insurance makes a key difference in whether, when, and where people get medical care and ultimately how healthy they are. Studies repeatedly demonstrate that those without insurance are less likely than those with insurance to receive preventive care and services for major health conditions and chronic diseases.[2] Medical bills can put great strain on those without insurance and threaten their financial well-being.

Basebuilding organizers in our network advocate for healthcare justice by calling for improved access to affordable health insurance or Medicaid benefits. They also advocate to expand general health services to include culturally and linguistically appropriate services, food, nutrition, and wellness especially for student populations.

DISPARITIES AND STATISTICS

Race and Ethnicity:

Black reproductive health disparities are amongst the most alarming health disparities in the United States. Black people are more likely to have preterm births and 2-6 times as likely to die from complications of pregnancy than white people. Further, pregnancy complications influence disease risk in later life, such as a higher likelihood of diabetes among people who experience preterm births.[3] Levels of stress, trauma, food insecurity, access to prenatal care, and other social determinant of health conditions impacted by systemic racism and bias most likely account for these disparities.

Implicit bias among healthcare providers contributes to health disparities through patient-physician interactions amongst communities of color. Black patients report experiencing poorer communication and lower quality of care compared to white patients, Black patients seen in emergency departments receive less analgesia than white patients despite expressing their pain experience, and Hispanic patients are 7 times less likely to receive opioids in the emergency room than white patients with similar injuries.[4]

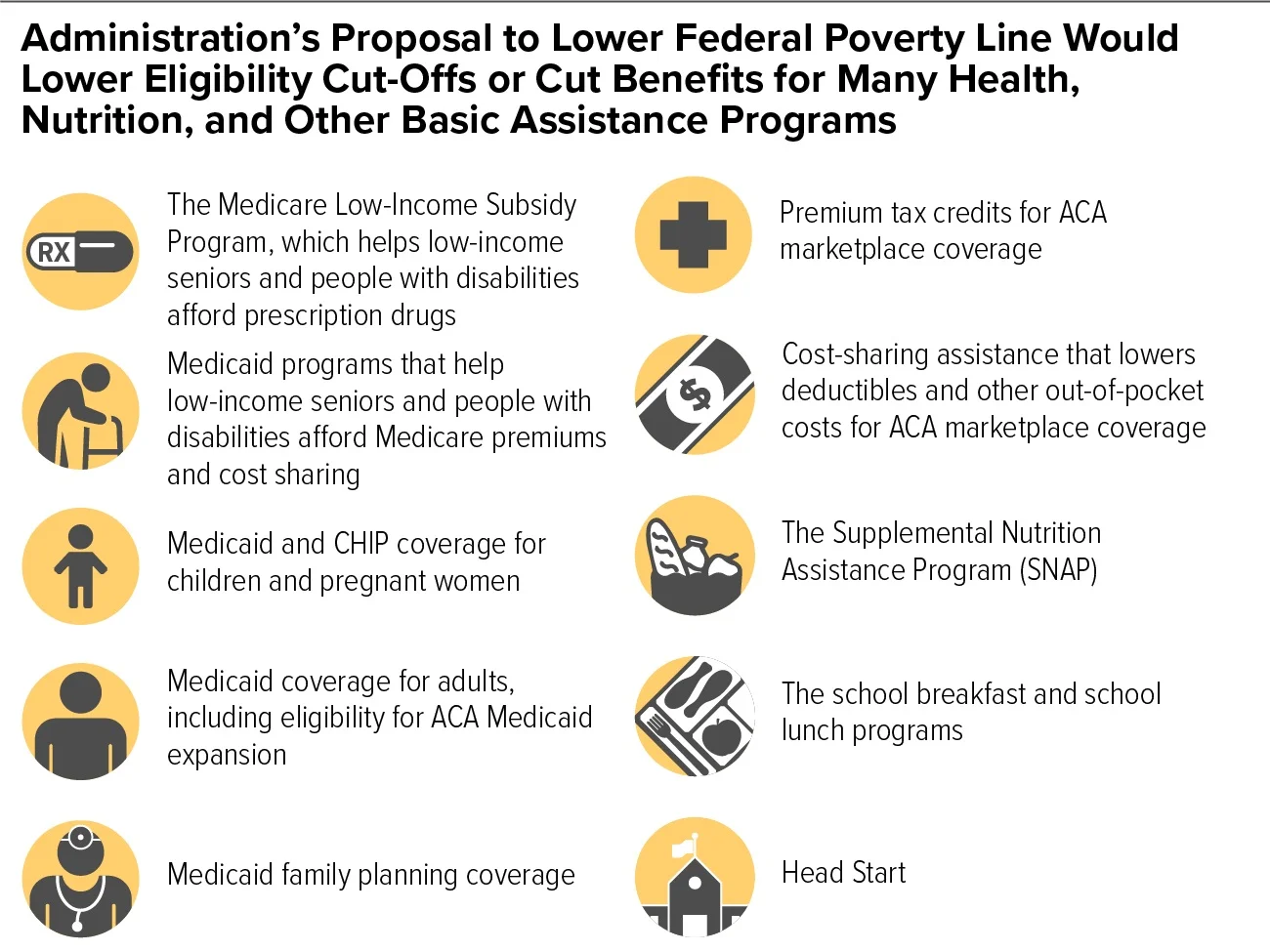

Structural factors such as implicit bias, privatization of care, and limited culturally relevant care contribute to inequitable access to health insurance.[5] In 2018, people of color were at higher risk of being uninsured than Whites. Hispanics and Blacks have significantly higher uninsured rates (19% and 11%, respectively) than Whites (8%). In states with Medicaid expansion, decreases in the uninsured rate were larger among communities of color compared to Whites, which helped narrow disparities in coverage.[6]

Socioeconomic Status:

Socioeconomic status is one of the most powerful predictors of disease, injury, and mortality in the United States. Adults with lower SES have life expectancies 7-8 years less than those who have income 4 or more times the federal poverty level. People in poverty are statistically at greater risk for disease, due to compounding social determinants of health factors that influence access to healthy foods, exposure to pollutions and toxins, safe neighborhoods, transportation, etc. Additionally, people with lower SES have less access to health services, including but not limited to dental care, specialists, mental health services, and medication.[7]

The rate of cost-related access barriers to healthcare has decreased for adults making less than $25,000 a year since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but continues to be a barrier to many. In 2016, 33% of adults did not fill a prescription, see a doctor when sick, or get recommended care because of prohibitive cost.[8]

Gender & Sexuality:

In 2020, the federal government eliminated explicit nondiscrimination protections for LGBT individuals in the Affordable Care Act, such as nondiscrimination standards for qualified health plans and the marketplaces. In 2020, it is estimated that half of the LGBTQ population lives in states that do not have LGBT-inclusive insurance protections.[9]